Brexit’s Toll: UK Defence Cuts Loom as the UK Looks to Reduce Budget Shortfall

With the UK’s 10-year military equipment plan under economic pressure, the Ministry of Defence is being forced to decide which capabilities to prioritize and which to potentially lose in order to balance the books due to Brexit’s economic impact.

This paper explores what kind of UK defence cuts might actually take effect should the cost-savings plans reportedly under consideration be put into place, as well as the possible rationale behind those cuts.

These options include the removal of the Royal Navy’s Landing Platform Docks (LPDs), HMS Bulwark and HMS Albion, a reduction in the number of Type-23 frigates and further cuts to the Army’s helicopter fleets and armoured vehicle programmes.

Barely one year into the UK’s major defence modernization plan, the MoD must once again revisit its military priorities. The result could be significant programme cuts to the armed forces.

Largely driven by Brexit budget shortfalls, the latest review is caught between a requirement to find £20 billion in savings and the MoD’s recent campaigning to ramp up defence spending.

The likely outcome is a further round of UK defence cuts focused on the Royal Navy and Army, with implications — such as the potential end of amphibious operations — for the nation’s security posture in the decades to come.

This shortfall is partially due to increased costs due to Brexit, with the pound’s fall against the US dollar raising the cost of buying American platforms such as the F-35B Lightning II and P-8A Maritime Reconnaissance Aircraft.

The 2015 UK Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) saw the UK Ministry of Defence repeatedly commit to a £24.4 billion increase in spending on equipment over 10 years, leading to the £178 billion Defence Equipment Plan being unveiled in 2016.

However, the UK faces the prospect of a budget shortfall that would restrict the MoD’s ability to fund key programmes. This shortfall is partially due to increased costs due to Brexit, with the pound’s fall against the US dollar raising the cost of buying American platforms such as the F-35B Lightning II and P-8A Maritime Reconnaissance Aircraft.

However, a significant portion of the £24.4 billion increase in spending was to be found through savings, rather than simply more investment. With the Ministry of Defence struggling to find the required £20 billion in savings, before the increased costs of procurement are considered, the UK now finds itself in the midst of a fresh review of national security capabilities.

This effort is being dubbed a “mini-SDSR.” Whilst MoD leaders had pushed for an increase in defence spending from the Treasury, under the current economic conditions this seems unlikely. As a result, it is far more likely that there will be a further round of cuts to key programmes.

During the review, each service will seek to defend its key priorities in exchange for sacrificing either current platforms or programmes in order to balance the books. What are the options for the Royal Navy, Army and the Air Force and what kind of impact will these cuts have on the UK’s ability to conduct military operations abroad?

Royal Navy

DUE TO HIGH SUPPORT COSTS IN RELATION TO PROCUREMENT, IT IS LIKELY THAT IN ORDER TO MAKE SAVINGS THE ROYAL NAVY RETIRE SHIPS EARLIER THAN EXPECTED

Possible UK defence cuts: Losing a ship or two – or much more?

The UK’s National Shipbuilding strategy, launched in September 2017, made it clear that the Royal Navy’s priorities into the next decade would be the Type 26 Frigate, Solid Support Ship and the creation of a new lighter frigate, the Type 31e.

Much was made of the drive to not only keep the cost of the Type-31e programme low, capped at £250 million per ship, but also to propel Britain into a position as a leading exporter of naval platforms.

Given this emphasis, it is unlikely that the current round of negotiations will see any of these programmes targeted for UK defense cuts. It is also almost inconceivable that the UK will compromise its submarine building programme.

The Astute Class is well under way and the procurement of the Dreadnaught Class of ballistic missile submarines represents a key strategic capability.

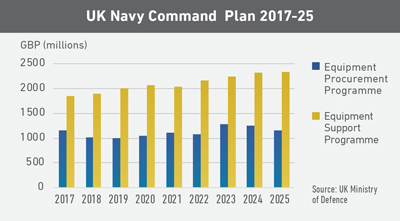

Given these assumptions, it is worth noting equipment support accounts for 65 percent of the Royal Navy’s planned £29.1 billion equipment spend. This means that either the temporary or permanent withdrawal of ships from service is a real possibility.

Such a solution is hardly new, with previous needs to reduce spending resulting in the early retirement of the UK’s carrier capability in the form of HMS Ark Royal and HMS Illustrious, decommissioned in 2011 and 2014 respectively.

HMS Albion has also been laid up for the past six years, with only the last two years being used for upgrades. The current plan is for HMS Albion to rotate with HMS Bulwark, leaving a single amphibious assault ship available whilst the other remains at extended readiness.

The decision by the Royal Navy to forego a carrier capability was a significant risk but a temporary one due to introduction of the Queen Elizabeth Class carrier.

Apart from the fact that the UK’s military response to Islamic State was limited to operations from Cyprus rather than being able to deploy an aircraft carrier to either the Mediterranean Sea or the Gulf, it could be argued that the gamble to withdraw the two aircraft carriers from service paid off.

The UK was still able to work as part of a coalition that provided aircraft carrier assets. From a practical perspective, the presence of RAF Akrotiri Station in Cyprus meant that a regional contribution could still be made.

The calculated risk worked in the short term but it would not be desirable for a long term given the UK’s ambitions to remain a global power. The two Queen Elizabeth Class carriers will likely remain on track despite their high cost.

However, the writing could be on the wall for the UK’s amphibious assault capabilities in the current review. In the argument over which ships, if any, ought to be removed from service, the Royal Navy’s Landing Platform Docks (LPDs) do not fare well.

However, the writing could be on the wall for the UK’s amphibious assault capabilities in the current review. In the argument over which ships, if any, ought to be removed from service, the Royal Navy’s Landing Platform Docks (LPDs) do not fare well.

A recognition of the fact that the UK could not afford to have fewer than 13 frigates in service led to the adoption of the Type-31e programme to augment the eight Type-26 frigates the UK deems affordable.

In fact, the hope is that more than five Type-31e ships could be procured in the future to boost the UK’s frigate and destroyer fleet to beyond 19 platforms.

One cost saving option would be to reduce the number of Type-26 ships, with only the first 3 under contract, and put greater emphasis on the Type 31e.

This would significantly reduce the capabilities of the Royal Navy to conduct surface warfare and it is almost certain that this option will be avoided.

A much more palatable alternative, at least to those in the Admiralty focused on a blue water navy, would be to sacrifice the Navy’s assault capabilities, removing both HMS Bulwark and HMS Albion from service. This would draw a significant amount of criticism due to the fact that HMS Bulwark has only just completed a £90 million refit before returning to the fleet.

It would also leave the UK with only a limited means to deploy an amphibious assault force. The Royal Fleet Auxiliary’s four Bay Class Landing Ship Docks can launch landing craft, however their capacity is greatly reduced compared to the Albion Class, with the latter able to carry four Landing Craft Utility (LCU) and four Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) Mk 5 craft.

By contrast the RFA Bay Class can carry either a single LCU or two LCVPs which means that two ships would be required to land even a company-sized element of Royal Marines.

If the Royal Navy were to lose most of its amphibious assault capability then questions would be raised whether this would be a temporary measure or a permanent acceptance that future assault landings would be by helicopter.

This was the case for the UK’s last coastal assault, with Chinook helicopters used in 2003 during the operation by 3 Commando brigade against the Al-Faw peninsula in Iraq. If the capability gap were to be temporary, the UK would either need to use funding to keep both platforms at extended readiness rather than decommissioning them, or plan for replacement platforms which are unlikely to enter service in the 2020s.

End of the amphibious era for the Royal Marines?

If the UK were to lose its ability to launch even a battalion or commando level beach assault, questions would then be raised about the future of the Royal Marines. As well as providing fleet protection, the Royal Marines have a proud history of conducting beach landings with Britain’s first marines conducting an opposed beach landing in 1692.

However, this capability has not been used operationally for more than 30 years, with the last landing taking place during the Falklands War in 1982. Instead more recent operations have been conducted via helicopter assault.

The UK is increasing its helicopter assault capability by using one of its Queen Elizabeth Class carriers which has greater capacity than HMS Ocean, due to retire from service in 2018.

The Royal Marines could maintain the capability to conduct low-level raids whilst working with allies to gain access to amphibious landing capabilities. For example, the Royal Marines could work alongside the US Marine Corps.

As their role in any landing force would be relatively small in comparison to a much larger US Marine Expeditionary Force, it would lead to further questions about the true need for a UK landing capacity.

A far more politically unpopular measure would be to reduce the strength of the Royal Marines with their role restricted to largely fleet protection and air-assault roles.

Such a cut has been feared for many times, especially in the light of reports that the force is already to lose 300 posts to free up personnel funds to crew HMS Queen Elizabeth. Any decision to remove HMS Bulwark and HMS Albion from service will only fuel these fears further.

Cutting even deeper – Type-23 in the crosshairs of the UK Defence Cuts

An argument can be made that the Royal Navy is able to meet its current operational and training demands with a reduced number of ships, whilst still being committed to a 19-ship surface combatant fleet in the future.

One option that appears to be on the table is the early retirement of a number of Type 23 Frigates. Jane’s Navy International recently reported that both Chile and Brazil have been informed that two Type 23 Frigates could become available for sale in 2018, with a further five in 2023.

This would initially reduce the number of destroyers and frigates in service from 19 to 17, with the number of frigates cut from 13 down to 11.

This may raises alarms at the prospect of the UK reducing its Navy even further, yet the fact is that in 2016 HMS Lancaster was placed in a state of extended readiness which effectively reduced the frigate fleet to 12, whilst at the same time HMS Westminster, HMS Montrose and HMS Argyll were being overhauled, returning to sea in 2017.

An argument can be made that the Royal Navy is able to meet its current operational and training demands with a reduced number of ships, whilst still being committed to a 19-ship surface combatant fleet in the future.

This would be achieved through the introduction of the Type-31e and then Type-26. The sale of two or more Type 23 frigates could be seen as an easier option, both politically and militarily, due to the fact that such a reduction in strength would be temporary.

Impact on the Royal Navy

THE SACRIFICING OF SHIPS IS A LIKELY OUTCOME GIVEN THE CURRENT BUDGET CONSTRAINTS.

Unless additional funding can be secured, the Royal Navy faces a stark choice between delaying procurement programmes or sacrificing capability by withdrawing ships from service with new UK defence cuts.

Whilst the prospect of losing amphibious assault capabilities may be difficult to fathom, the alternative could be far worse. Sacrificing HMS Bulwark and HMS Albion could ensure that sufficient funds remain available to complete the far more important procurement of a new fleet of frigates as well as the ships required to support a task force.

At the same time, the removal of a number of Type-23 frigates from service could be a way of creating enough savings without having to cut both LPDs.

The fact that the UK seems unlikely to reduce the scale of either the Type-31e or Type-26 means that the question has become more about which ships will be removed from service, rather than if any will be removed at all.

British Army

THE LOWER PROPORTION OF SUPPORT FUNDING FOR THE ARMY COULD LEAVE PROCUREMENT PROGRAMMES VULNERABLE

Possible UK defence cuts: Procurement delays and helicopter reductions?

Possible UK defence cuts: Procurement delays and helicopter reductions?

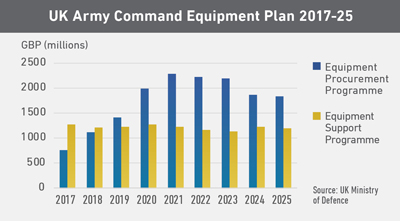

The British Army finds itself in a different position to the Royal Navy, with planned spending on equipment procurement accounting for 58.9 percent of its portion of the equipment plan.

From April 2016 to April 2026 a total of £15.69 billion has been planned for either the procurement of new equipment or for major upgrade programmes, with £10.94 billion set aside for equipment support.

The Army is currently in the process of a major re-organization that will see the UK’s main fighting force centered around 3rd Division. It will have two armoured brigades based around the Challenger 2 Main Battle Tank and Warrior Infantry Fighting Vehicle and two Strike brigades utilizing the new Ajax family of tracked reconnaissance vehicles and the wheeled Mechanized Infantry Vehicle (MIV).

For this structure to be a credible force, investment must be maintained for all four platforms. The Ajax family is currently in production under a programme that will cost £5.4 billion whilst a decision to move from the development phase into production for the Warrior Capability Sustainment Programme (CSP) will be taken soon.

The Ministry of Defence could achieve savings on Warrior CSP by looking to re-compete the production phase of the programme, once again pitting BAE Systems against Lockheed Martin UK; Lockheed won the demonstration-phase contract.

However, this would have to be weighed against any time delays, as the upgrade is long overdue. The need to enable the first strike brigade to achieve initial operating capability in 2023 means that the opposite approach could be taken for the MIV with the potential for a single source acquisition strategy that would see ARTEC’s Boxer being procured.

Under the current budget climate, reports that up to 800 Boxer vehicles could be ordered are likely to prove unrealistic, as the procurement of even 400 vehicles would cost more than £2 billion.

Critics have argued that the selection of Boxer does not represent value for money and that a competition should take place which would attract bids from suppliers such as KNDS (VBCI), Patria (AMV) and General Dynamics (Piranha V).

An argument against this approach would be that the procurement process would take longer. At the same time ARTEC have been keen to make clear around 60% of the work will be carried out by UK companies.

The Army has stated that upgrading its Challenger 2 fleet is one of its key priorities, however it appears the most likely to suffer delays with its upgrade programme due to repeated delays over the past 10 years and the fact that the process remains in the assessment phase.

Despite the Challenger 2 upgrade seeming more vulnerable in comparison to work on the other vehicles that will form the core of the UK’s land warfare capability, it is unlikely that any will face delays. Instead it is more probable that the Army will look to other areas of procurement and support for savings.

Despite the Challenger 2 upgrade seeming more vulnerable in comparison to work on the other vehicles that will form the core of the UK’s land warfare capability, it is unlikely that any will face delays. Instead it is more probable that the Army will look to other areas of procurement and support for savings.

Traditionally when UK defence cuts have been made to the Army’s procurement programmes, the victims have been combat support and combat service support.

Despite the fact that the UK is pressing to improve its indirect fire capabilities, it seems unlikely that the Royal Artillery will be able to secure the funding it requires to modernize its inventory, relying instead on the AS90 155 mm self-propelled howitzer for the armoured brigades and the L118 105 mm light gun for air assault.

What this will do is leave an obvious capability gap for the Strike brigades, with the requirement for a wheeled howitzer yet to be fulfilled. The other area that could see potential delays is the next phase of the Multi-Role Vehicle-Protected programme. By procuring a larger-than-expected number of Joint Light Tactical Vehicles (JLTVs), under a US Foreign Military Sale valued at $1.04 billion, it is possible that the Army’s Category 2 6 x 6 vehicle could be delayed and the current fleet of vehicles retained instead.

The main UK defence cuts for the Army appear to be to the Army Air Corps. The helicopter force could be reduced by five squadrons, reducing the strength by 400 roles as well as 200 support positions.

The fleet of 34 Gazelle helicopters is also expected to be removed from service, generating further savings in terms of equipment support. At the same time there is no guarantee the Army’s Lynx Mk 9A helicopters will be replaced by the new Wildcat Mk 1 when they are withdrawn from service.

Impact on the Army

The importance of Warrior vehicles was demonstrated in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and if the platform were to be unavailable this would be as disastrous to the army’s ability to operate as the loss of frigates would be to the Navy.

The proposed future structure of the British Army is dependent on the procurement of new platforms in the form of the MIV and Ajax vehicles. At the same time, a reduction in the number of armoured brigades means those remaining units must be equipped with modernized vehicles.

Any delays to the Warrior CSP and Challenger 2 Life Extension Programme would mean that the UK would be overly dependent on its medium forces. The importance of Warrior vehicles was demonstrated in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and if the platform were to be unavailable this would be as disastrous to the army’s ability to operate as the loss of frigates would be to the Navy.

On the other hand, the Army could get by with its current fleet of support platforms for a number of additional years and many Army Air Corps missions can be performed by the RAF’s rotary platforms.

Royal Air Force

DUE TO THE HIGH USEAGE OF THE RAF’S FLEET, IT SEEMS LESS LIKELY THAT CUTS WILL BE MADE TO AIRCRAFT.

Possible UK defence cuts: An intact fleet, but aircraft availability may suffer

The Royal Air Force looks the least likely of the three services to suffer significant UK defence cuts. Strong cases exist for both the continued procurement of Typhoon aircraft and the F-35B, which is due to enter service soon.

The Royal Air Force looks the least likely of the three services to suffer significant UK defence cuts. Strong cases exist for both the continued procurement of Typhoon aircraft and the F-35B, which is due to enter service soon.

The UK’s air assets played a central role in Operation Shader, which saw Typhoon and Tornado fighters together with Reaper unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) conducting airstrikes on Islamic State targets in Iraq and Syria. Support assets such as the Voyager tanker aircraft also played a key role and it is difficult to identify any capabilities vulnerable to cutbacks because of their operational essentiality.

The procurement of P-8A Maritime Patrol Aircraft to replace the retired Nimrod fleet is likely to continue, despite current disagreements between the UK government and Boeing over recent tariffs levied on Boeing’s smaller commercial rival, Bombardier.

The area where savings are most likely to be made in the equipment support budget is in terms of availability. It may become acceptable to have fewer aircraft available at any one time to reduce support costs.

This risks the RAF’s operational tempo in Operation Shader, however with the demise of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria in recent months it could be argued that the pace of operations will slow anyway. This will put less demand on the Tornado GR4 fleet, with the aircraft to be removed from service in 2018 and 2019.

One option open to the RAF would be to disband as many as all three Tornado squadrons and retire the aircraft early. This would however pose a potential capability gap as the Typhoon Centurion upgrade is not yet completed and there would be a limited number of aircraft able to deploy Brimstone and Storm Shadow missiles.

Impact on the RAF

At a time when the usage of RAF assets has been so high over Iraq and Syria, it is difficult to envision significant equipment cuts being tabled in the UK defence cuts. It is therefore expected that the strategic review’s impact on the RAF will be limited. However, there could be reduced readiness due to fewer flying hours if some form of savings is required by the service.

Tough Decisions Made Tougher by Brexit

For this reason, the early retirement of platforms or sacrificing of lower priority programmes looks increasingly probable as officials aim to ensure that the majority of the objectives laid out in the equipment plan can be achieved.

Tough Decisions Made Tougher by Brexit

Without an increase to defence spending it seems impossible that procurement plans will be able to be achieved without significant cuts. Whilst savings are being found through reductions in areas such as training and readiness, more visible actions will likely need to be taken.

These savings could be achieved through short-term measures such as the early retirement and re-sale of Type-23 frigates. On the other hand, a more significant drawdown in capability could take place, centered around the ability to conduct amphibious landings and sustained long term land operations due to a shortage of support platforms.

This loss of capability is likely to emerge as more viable option than compromising the UK’s ability to conduct a much broader mixture of operations by restricting new acquisitions. For this reason, the early retirement of platforms or sacrificing of lower priority programmes looks increasingly probable as officials aim to ensure that the majority of the objectives laid out in the equipment plan can be achieved.

No matter where the review of national security capabilities decides to make savings, the UK needs to determine exactly what roles its armed forces can and cannot perform. Tough decisions will need to be made, which could be increasingly tougher if the economic impact of Brexit worsens.

It is unlikely that this will be achieved without a full SDSR, with this review instead appearing to be more about cost savings. The main risk is that the review will try and maintain a wide-ranging strategy whilst reducing the capabilities on hand with which to meet strategic objectives as the goals of the Treasury, Ministry of Defence and Foreign Office collide with these UK defence cuts.

Image Source:

- Photo 1: Pictured is HMS St Albans taking part in a rare double Replenishment At Sea (RAS) with the German Tanker FGS Spessart and the Norwegian Frigate HNoMS Roald Admundson, all this whilst continuing to escort the Russian Carrier Task Group through British areas of interest. Photo couurtesy of Dave Jenkins, MoD/Crown copyright 2017.

- Photo 2: Britain’s future flagship HMS Queen Elizabeth sailed into her home port of Portsmouth for the first time. Photo couurtesy of Dan Rosenbaum, MoD/Crown copyright 2017.

- Photo 3: HMS Sutherland keeping a watchful eye on a Russian ship transiting through UK territorial waters. Photo couurtesy of Donny Osmond, MoD/Crown copyright 2016.

- Photo 4: Pictured are members of the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment (HCMR) on the Mall as the Army celebrate the birthday of their Queen. Photo couurtesy of Owen Cooban, MoD/Crown copyright 2016.

- Photo 5: On Friday 1st July 2016, a pair of F-35B’s, Lightning II jets of the Royal Air Force and USMC took part in some formation flying over the east coast of England. Photo couurtesy of Tim Laurence, MoD/Crown copyright 2017.[divider]